Did the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Cause the Great Depression?

Probably not, but it cost the economy a lot of money

Congress passed the most famous tariff law in American history, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, in June 1930. By then, the economy was already in a recession.

Over 1,000 economists urged President Herbert Hoover to veto the law. He did not.

Here’s the story of why — and what happened next.

The Republican Policy of “America First”

From the 1920s to the 1940s, the United States turned inward in three steps.

First, immigration. After decades of welcoming immigrants by the millions, Congress passed two laws — in 1921 and 1924 — that imposed strict quotas limiting the inflows.

Many legislators and their constituents hoped that the quotas would reduce labor competition and free up jobs for US-born workers. They did not. Often, the quotas actually forced companies to cut production and lose money.

Second, trade. According to a recent analysis by the economist Jeff Chan, the same legislators — the ones who voted to restrict immigration — tended to vote for the Smoot-Hawley Tariff too. In fact, he says, “districts that were anti-immigrant in their Congressional voting earlier [became] more entrenched in their nativist attitudes.”

Chan’s study shows that this voting bloc — anti-immigrant in 1921 and 1924, anti-trade in 1930 — was almost entirely Republican. In supporting the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, President Hoover was keeping in line with his party’s “America First” policy.

Third, foreign policy. By 1940, this worldview inspired the “America First Committee,” made up of 800,000 members, including many prominent politicians, business leaders, and celebrities, who opposed American intervention in World War II.

Hoover himself wasn’t a member of the America First Committee, but his tariff policy had emerged from the same movement to erect barriers to global cooperation.

Impact #1: Consumers Paid for It

Back then, the United States didn’t trade as much as it does today. In the 1920s, Americans only spent 4 percent of the national income on imports from abroad. Today, we spend 14 percent.

By the time the Smoot-Hawley tariff hit the global markets, that import volume was already falling even further. As the economy contracted, so did our ability to buy things from overseas.

But Smoot-Hawley definitely made it worse.

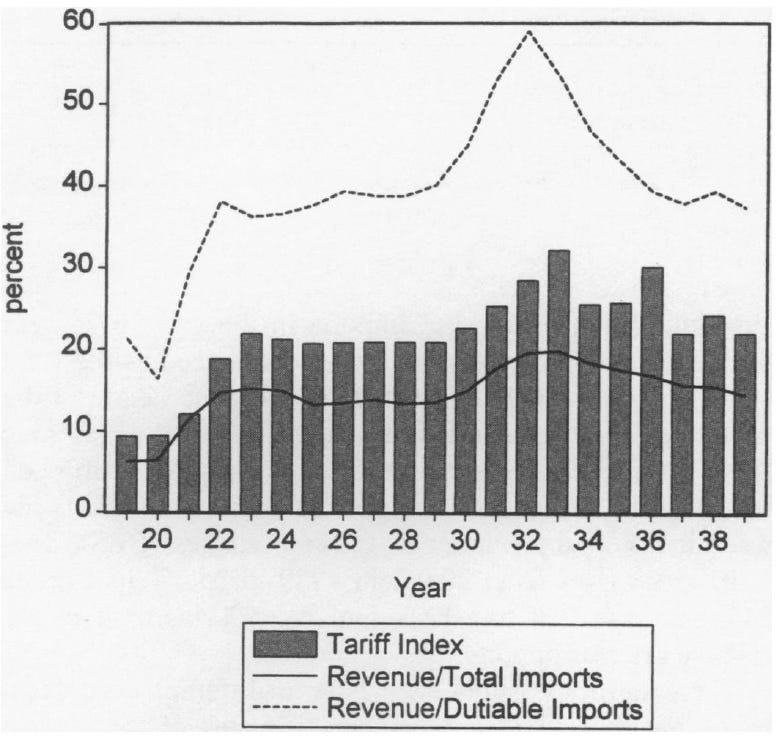

Tariff rates were already high by today’s standards, but Smoot-Hawley pushed them over 22 percentage points higher, on average, across all industries.

According to the economist Douglas Irwin’s calculations, consumers wound up paying about 5 to 6 percent higher prices as a result. Weighing that impact against the industries that benefited from the tariff, the economy lost more national income than it gained, on net.

Impact #2: Productive Firms Paid for It

Just like today, there wasn’t only one tariff back then. The Smoot-Hawley Act imposed different tax rates on different industries. So, it raised prices for some firms more than others.

It particularly hurt the economy’s most productive firms — and therefore, it scared consumers and investors away from these top producers.

As a result, economists have found, the Smoot-Hawley tariff shifted the nation’s money into less productive investments and reduced the overall productivity of the U.S. economy.

Impact #3: Exporters Paid for It

And just like today, America’s trading partners fought back. Almost all of them filed a formal protest with the State Department and reduced their imports from the United States by 15 to 23 percent. Nine countries went further and imposed retaliatory tariffs targeting our most important exports, particularly automobiles.

Back then, exports only accounted for 4 percent of the economy. Based on recent calculations by Kris James Mitchener, Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke, and Kirsten Wandschneider, the retaliation probably cost 1 of those 4 percentage points.

Combining those losses with the consumer losses and the productivity losses, the tariff was probably enough to tip the economy into recession — but nowhere near the full magnitude of the Great Depression that was underway.

Today, with exports fueling 11 percent of our economy, cutting back on exports by the same proportion would cost us a lot more.

The Long Road to Bipartisan Trade Policy

Despite these losses, the Republican Party stuck to its protectionist agenda throughout the 1930s.

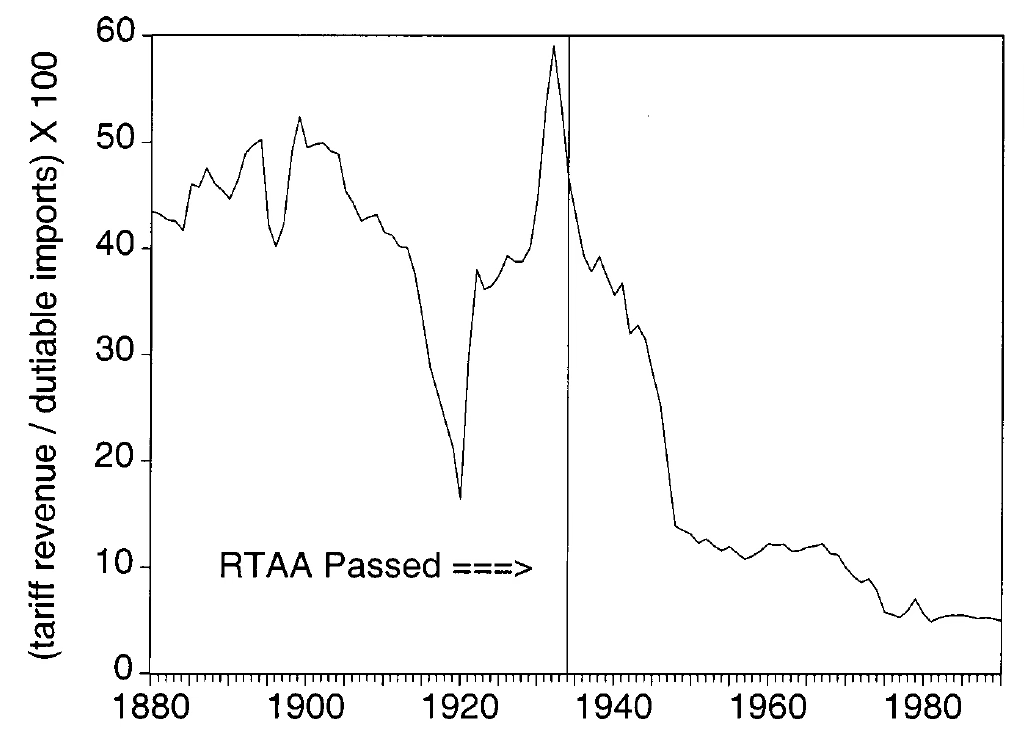

When Democrats rose to power, they reversed course with the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) of 1934, which gave the president the authority to negotiate free trade agreements — reducing tariffs and other trade barriers — without Congressional approval. The bill had to overcome strong Republican opposition.

When the economists Douglas Irwin and Randall Kroszner reviewed the voting record, they found that “not a single Republican senator voted in favor of renewing the RTAA in 1937 and 1940.”

In fact, the official Republican Party platform vowed to repeal the RTAA, but they couldn’t take back the White House for 20 years.

But in the 1940s, something changed. With the end of high tariffs, exports grew — and exporting firms started to play a bigger role in politics.

In 1945, Republicans in high-export states began crossing the aisle to vote with Democrats in renewing the RTAA. The “America First” era was officially over.

The bipartisan era of lowering trade barriers had begun.